Who am I?

I,

I’m my thoughts,

My dreams,

My aspirations.

I’m my name,

My looks,

My imagination.

That’s what I see,

When I stare,

Into my reflection.

My reflection,

Ripples in the river of life,

The shallow,

Shallow river of life.

To the world,

I am my reflection:

I am only what the world sees,

Only what the world decides I am.

My body is but a vessel;

Why must the world ignore me,

But acknowledge the vessel?!

Books, merely objects

Are still judged

By only their covers,

So who am I to demand

They not judge me

By only what they can see.

The inside of a book

Is where the value lies

But most people don’t bother;

It’s easier to judge

From the outside

My body is a part of me,

It embodies my soul

My personality,

But it is not all I am.

I am not my scars,

My disability,

I am me,

A completely separate entity.

I, Me,

Not just what you see

disabled bodies

His little world

I wanted to talk about my family friend’s son named Shaun. I’ve known Shaun for a while, he was really young when I met him, I was still young however, in my middle school years I was still learning things. Shaun, along with his brother Stefon were autistic. Whenever it came to the family parties I would be the one to watch over them and keep them company since I was still young and couldn’t be a part of the adult or even the teenage conversations. Shaun was an interesting kid, although he didn’t communicate verbally with words, I felt like I could still understand him and what he needed. I felt like I could understand his emotions.

Shaun would always get in trouble for breaking things, but I knew it was him just stimming because that was one of his habits. I remember during a Christmas party he grabbed one of the ornaments from the tree and smashed one to the ground, and then another, several times until he was stopped by his mother. Shaun got in trouble with his mother. I felt bad for him, I knew he wasn’t doing it to make anyone mad, yet his mom did get mad at him for doing it anyway since it wasn’t his house. She looked defeated, like she didn’t know how else to help him whenever his behavior would get worse. She looked tired too, like she was doing everything she can to just enjoy her time at the party and also watching her boys making sure they didn’t break anything or do something dangerous. My parents loved Shaun and his brother, my dad always made an effort to let Shaun be seen, playing with him, making jokes and funny faces. Whenever Shaun was with me, I tried my best to entertain him, to make him feel heard. He always had a fascination with my hair (back then I used to have hair that would reach the floor I had to keep it in a braid since it was so long, I’m not kidding haha) so every time we sat in a room to calm him down he would touch it and slowly begin to settle. The way he felt my hair and stared at it gave me a sense of comfort knowing that I was there with him making sure he was okay. He would hum the majority of the time, whenever he wanted something he would hum in a pattern and point at the object that he wanted. Shaun never had good focus either, after touching one object he would go onto the next and then the next. Shaun’s mom works with other children who are autistic, whenever she would come to these parties, she would bring books for them to read, I would read the books to Shaun and his brother. Shaun was always mesmerized by the images in the books, he would hum and point at the characters. He always made me feel like whatever I was doing was helping him and that gave me a deep sense of reassurance.

Sean was very excited about noises but more specifically with car keys. Whenever it came to these parties or Mass services because we do services in different people’s homes, Shaun would actually find people’s keys and take them and play with them because he loved the sound of the jingling. My dad didn’t care, he would give Shaun his keys so he could be happy and play with them. Of course he didn’t know any better because he didn’t understand the ownership of somebody’s property. I always felt like the adults who would get their keys taken away wouldn’t truly understand how happy it made him. They would just get a little frustrated because of the fact that their property was taken away from them. I definitely think being in middle school and being exposed to that environment where somebody has a disability made me confused at first because back then I didn’t know the true meaning of autism and the levels and how there’s a spectrum. I only got to see the behaviors and patterns of somebody with it during that time, but now being an adult and learning more about autism and neurodivergence I slowly start to understand Shaun and his behavior. He just wanted to be understood because of his different way of thinking. Unfortunately due to family issues in the past I haven’t seen Shaun in a while but I hope right now since he is older that he’s getting the proper care and going through a more suitable way of teaching for him to understand. I really do think Shaun is a good kid.

I just feel like people are always afraid to try to communicate with people who have this disability because they don’t understand the way autism works and the levels of the spectrum. Every time I see a child with autism, or introduced to someone, I am never afraid to interact or learn from them, because with Shaun, all I ever did was make him feel heard and safe, and I want to do that for every other boy or girl who has autism. Society likes to put this negative connotation and label of people with disabilities which to me is just undermining their true potential and power, I learned a lot from Shaun and my other experiences after that, and seeing how their minds think and interact made me open my eyes to a whole different concept of learning and understanding. I learned more patience, I learned to really slow down my “normal” thinking and try and fit their perspective into my life. Doing that type of thinking really does open up your mind to a lot of ideas and thoughts. I am thankful for Shaun and the way I made him feel comforted and cared for, that’s something I won’t ever forget. I do know his parents were really good when it came to teaching him, but just like Shaun and other kids who have it I hope the world is able to see that there is nothing wrong with them they just have a different perspective which isn’t and shouldn’t be seen as a negative thing.

What about the “right-to-live?”

I remember when Jahi McMath died—for the second time.

Senior year of high school, I came across an article about Jahi McMath, a 13-year-old Black girl who was declared brain dead after her tonsils were removed. It was Jahi’s first surgery, and she was scared. She didn’t want to go through with it, but her mom convinced her it would make her life easier (Jahi had sleep apnea, and removing her enlarged tonsils was intended to help). After speaking with the doctor, Jahi consented to the surgery, and she was fine for about an hour afterwards.

Jahi’s blood vessels were unusually close to the surface of her throat; the doctor had noted this in his chart for her, but the post-op staff was unaware. So when Jahi started coughing up blood, they didn’t see it as the alarm that it was, although Jahi’s family did. They repeatedly raised the alarms for her, but no one listened until her heart stopped.

Jahi was declared brain dead; her brain had stopped functioning due to the massive blood loss. In California, brain death is legal death. But Jahi’s family didn’t accept that. Her mother, Nailah, was convinced Jahi was still alive; Jahi responded to some stimuli and questions. Nailah asked Jahi if she wanted to be taken off life support, and Jahi said no through physical movements her mother taught her.

In the long legal battle that followed, Nailah and her family were forced to flee the state with Jahi under threat of legal action and jail time. Nailah’s insistence that Jahi was alive, and refusal to take her off life support, violated California’s medical ethics, so they went to New Jersey, where families can reject the notion of brain death on religious grounds—Nailah technically “kidnapped” Jahi to do this. There, Jahi had at-home around-the-clock medical support from nurses and doctors who were willing to lose their medical license or be shunned from the medical community; the doctors that treated Jahi were treated as quacks by the medical community. In the view of the community at large, you cannot treat a body that is already dead, and although Jahi’s body was not dead, her brain technically was. The California hospital where Jahi had been declared dead consistently disavowed the McMath family’s efforts and actively disparaged them for “desecrating a body.” But they were wrong.

With consistent care, and rogue researchers willing to look into her case, Jahi was able to exhibit signs of life, brainwave activity, and even underwent puberty. In 2017, a neurologist at UCLA independently confirmed that Jahi was no longer “brain dead.”

Jahi died—for the final time—in June of 2018, not even six months after the New Yorker article was published due to internal bleeding from abdominal complications. Despite overwhelming evidence, the hospital that issued Jahi’s death certificate refused to ever accept Jahi’s recovery and overturn her death certificate.

In 2020, I, much like Jahi, was preparing to go into surgery to get my tonsils removed for sleep apnea, just as she had been. Her name haunted the back of my mind in the days counting down to my surgery, but I, just like Jahi, spoke with my surgeon and asked him how many times he had done the surgery, what the risks were, how long he had been a surgeon. I had the insight that a 20-year-old had and a 13-year-old didn’t, but we were in the beginning of a pandemic, in the middle of the shutdown, and my mom wasn’t even allowed in the waiting room with me. Though I was nearly certain I would be fine (my surgeon routinely did much more complex and precise surgeries, like removing tumors that had grown into the blood vessels of the throat), I was alone when I frantically pulled the anesthesiologist aside and had to shamefully admit that I had been taking quinine pills until yesterday morning, a stupid superstition I had bought into as a way to stave off a Covid infection.

Quinine, for those unaware, is an herbal supplement that used to be used as a “cure all” back in the days of the Black Plague and the Spanish Flu. It didn’t work back then, but I’m a big believer in the placebo effect, and I needed to take something to put my mind at ease. One of the side effects of quinine—that I didn’t know until the morning before my surgery when I actually read the bottle—is that it can thin your blood. This makes you a higher risk for surgery; you’re more likely to bleed uncontrollably because the blood is much harder to coagulate. The bottle said to stop taking quinine two weeks before surgery. Feeling like I was going to cry, and possibly even about to die, I waited anxiously to be taken back and prayed that I would wake up afterwards.

Obviously, I did, or I wouldn’t be writing this right now. But I’m aware how lucky I was, and am. Jahi’s case is in direct opposition to Terry Schiavo’s: Terry Schiavo was a White woman declared brain dead who the hospital refused to stop treating, whereas Jahi was falsely declared brain dead and refused further treatment. Jahi’s family noticed this too; they knew if Jahi had been White, she would have likely received the attention she needed, and even if she had still been declared brain dead, her family’s choices would have been respected. Having come after both of them, and being light-skinned myself, I know my family would have had the respect and space they needed to make whatever decision for me they felt was right if my surgery had gone wrong.

Still, it haunts me; Jahi’s story is barely told outside of fringe medical pieces, but Terry Schiavo’s is well-known enough to be casually referenced in feminist writings. Who gets the right-to-live? Who is allowed to die? Why are our bodies’ needs and wishes ignored depending on the kind of body we inhabit? I hope Jahi is resting peacefully now, but I carry the anger and fear of what was allowed to happen to her.

Excerpts from my investigation into disability on campus

The following is a series of excerpts for an article that I wrote for The Retriever that was published on Wednesday. (Below is from my original draft, some changes have been made in the final version for newspaper formatting.) If these tidbits interest you, you can find the whole article in print on campus now!

UMBC, I have a challenge for you.

Administration, Student Disability Services, and Facilities all tout the campus accessible routes map as the end-all, be-all solution for disabled students navigating campus. My challenge for you is this:

Make your way to the stadium lot, and then walk to the Fine Arts Building using only routes labeled as accessible. You are not allowed to use stairs, though you may use the short cuts available through buildings via elevators. (The elevator short cuts are labeled on the map below.) For extra credit, start at the top of the hill near the Walker Apartments and go to the library.

I have marked the destinations for you below. The full map is available here: https://about.umbc.edu/files/2021/09/2021-UMBC-accessible-routes-map.pdf

While you are walking, focus in on your body. Ask yourself: What would this walk be like if my calves were screaming in pain? What if I struggled with balance and were prone to tripping on uneven surfaces and could fall? What if I were using a walker right now? What about a non-motorized wheelchair?

What about crutches, or a lower-limb cast? When you arrive at your destination, take a note of the time. How long did it take you compared to using the stairs? Did you have to use a new route compared to your ordinary routine?

It was disclosed to me by several students that after they met all of the (stringent and privilege-laden) requirements to receive an accommodation appointment with SDS, they are told they will be unable to get the accommodations they need. In addition, it has also been reported to me that these meetings are often negative in nature with the student seeking accommodations being met with derision and/or hostility for their accommodation requests. One student, who wishes to remain anonymous, reported being “refused note-taking assistance because they needed to ‘learn how to take notes themselves,’” as well as being refused alternative text formatting as that is up to the teacher and “they cannot do anything about it.” The student accurately pointed out that both of these accommodations are among the published list on the SDS website. Another anonymous student trying to receive accommodations was told, “I know migraines can hurt sometimes but that doesn’t mean you can miss class.”

Many of the interactions that were shared with me have a common thread that is heard all too often by the disabled community: “You’re just not trying hard enough” or “It can’t be that bad”. The implications that we are lazy, that we haven’t developed strategies to succeed in our classes, or that we are somehow exaggerating our health problems are not only outdated ways of thinking about disability but are also extremely harmful. The reality of our lives is that it frequently is “that bad,” and that we wouldn’t be asking UMBC for help if we hadn’t already exhausted all of the resources available to us as individuals. To hear these words from the people put in place to help us succeed is equivalent to lifting us up only to kick us back down. UMBC is not the only institution in Maryland struggling with this problem, as this article (https://www.jhunewsletter.com/article/2021/08/disability-isnt-taken-seriously- at-hopkins) written by a graduate student at Johns Hopkins details out. Laurel Maury was awarded accommodations by JHU but found that her professors refused to use them (even under threat of legal action) and some went as far as to bully her for having them. Maury’s struggle echoes many of the sentiments that have been expressed to me by current UMBC students.

To my fellow disabled students: You are not alone, you have a voice, and your voice deserves to be heard.

Bedroom.

2011 was the year I began distancing. By which I mean, I began a life lived from my twin bed, fueled by goldfish crackers and electrolyte drinks, seldom able to access the outside world. It wasn’t mine to call home anymore.

I was drowning in conditions that these doctors hardly knew about. I had no choice but to become my own doctor, nurse, and historian. More than anything, I became my own community.

The outside world was stolen from me by sickness, uncertainty, and administrative violence – this world was never built for my survival. Such predicaments were met with constant calls to push through – go into the world anyways, risk it all for a “normal” life. They said adapting to it would make me better. It wrecked my body and my mind. Being bedridden was extraordinarily taxing and painful in a way that cannot be understood by those who have not been fully immersed in it in this way, yet. But I am inseparable from my bedroom life, I am made of soft pillows and the world I built among them.

Continue readingthe horror of childhood

Last week, I woke up from a nightmare about being a child again. Ever since then, I’ve been thinking a lot about how being a legal minor was terrifying and frightening.

Continue readingExposed (TW: OCD, Perfectionism, Bugs)

If anything has debunked the mind-body split for me, it’s living with OCD. My obsessions are felt as deeply as they are thought. Every day I physically feel my compulsions begging for my submission. In resisting them, my body is flooded with a deep, gnawing unrest.

The normalization of perfectionism convinced me that my OCD was good for me. I looked good on paper – but I see no paper in my skin, my blood, my brain, my bones. I have learned that to save this body, I cannot give everything my best. “Just right” can never be achieved so long as I am the judge. The goalpost moves too quickly to register.

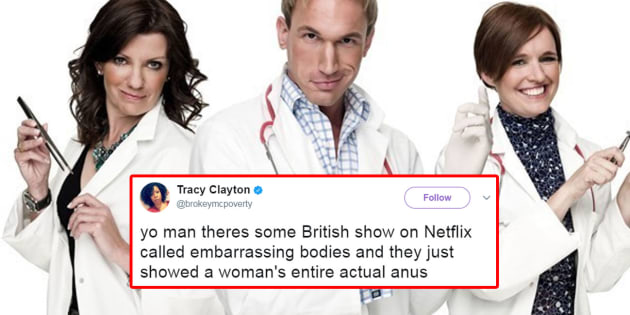

Continue readingShould You Binge-Watch Embarrassing Bodies?

Netflix now carries the British series: Embarrassing Bodies, a show about three doctors who travel through Britain, opening pop-up clinics for passersby seeking cures for a wide array of ailments or deformities. The show documents one-on-one consults, large group Q and A sessions on specific health-related topics (these are often set in schools, pubs, or other common public gathering places), street interviews on topics such as “baldness” or “boobs” and exhibits set up outside the medical tents where people can learn more about the inner workings of the body. All of these interventions are designed to make people less worried about their bodies, while setting up expectations about what is “normal” versus what requires medical intervention.

It is hard to think of an American equivalent of this show, though there have been other international spin-offs: Wikipedia lists Embarrassing Bodies Down Under, Dit is mijn lijf (This is my body) in the Netherlands and the strikingly named Я соромлюсь свого тіла (“I’m ashamed of my body”) in the Ukraine.

This Sucks

I remember talking to my mom about the book I was reading, “Feminist Queer Crip” by Alison Kafer. When I talked to my mother about disability, she pointed to an experience in her past. She said, she remembered back in her country seeing a man without legs or arms in the streets with a sign that asked others for food. My mom made a point to tell me that the man wasn’t sad, but was singing about the glory of God. Continue reading

Disabled people and pleasure

I had a conversation with people I was close with about nurses who help disabled people find sexual pleasure. Someone brought up a documentary about the nurses who do this and I offered that I heard a little about it in my Unruly Bodies class. I told them briefly about our section on disabled bodies and the things we’ve discussed in class. Continue reading